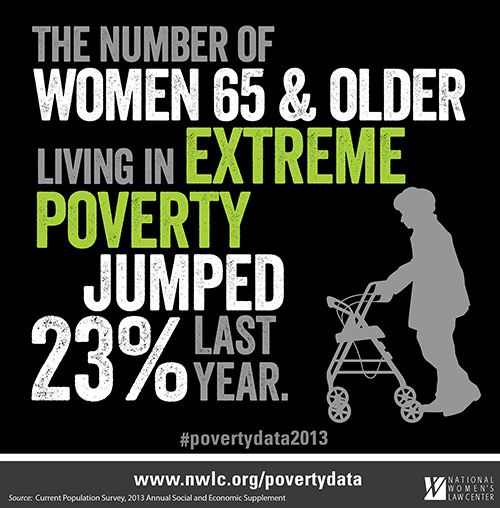

It is an unsettling prospect to realise that women face a significant risk of experiencing poverty in their retirement years. Older single women are one of the fastest growing groups of Australians living in poverty, and this is but the tip of a much bigger problem with no easy solution.

The report “Accumulating poverty”[1] released by the Australian Human Rights Commission (‘AHRC’) states that as things presently stand, superannuation payouts for women are around half that for men[2]. More troubling, is that in the current system, this difference in superannuation payouts will only get worse for the next generations of women[3]. This imbalance, through the various factors of income inequality, will hit hardest those women who will seek to rely on the means tested aged pension system as their primary source of income and support in their retirement years.

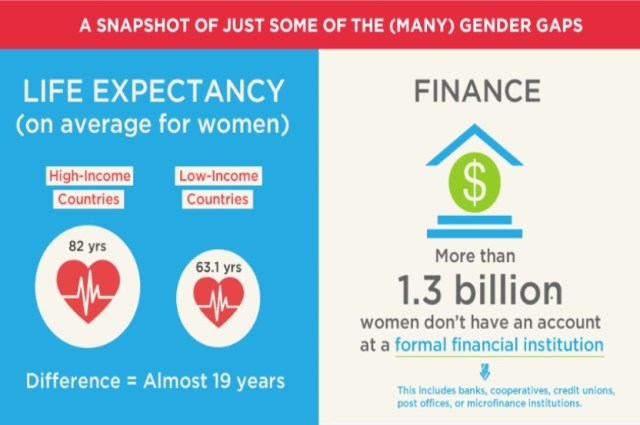

The simple cornerstone of this issue is that women have longer life expectancies than men, so from a practical perspective really require higher superannuation balances to provide for their needs, and care, for the remainder of their lives. More young females invest in their own futures by undertaking tertiary education, but they don’t see the same return on investment as their male counterparts.

A well documented factor in the shortcomings of retirement savings for women in Australia is of course the gender pay gap. Historically, we know that female dominated industries seem to attract lower wages than that of male dominated industries.

(Source: The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women)

(Source: The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women)

Let’s look at our own profession. A February 2018 Grad Stats report released by GraduateOpportunities.com reveals that of law graduates aged under 25, females are being paid an average of 8% less than their male counterparts. The median average in male and female graduate salaries showed a 1.5% disparity. For young women in the legal profession, the numbers show that they are 5.3 times worse off than the average.

As the Australian Human Rights Commission in their submission to the Senate Committee discovered the following statistics:

“In 2011, women comprised 56.5 per cent of the 2.23 million recipients of the age pension. Just over half (53.6 percent) of female age pension recipients were single and 71.8 percent of single age pension recipients are women. Sixty-one percent of female age pensioners received the maximum rate, and 27.3 percent were not home owners”[4]

The disparity continues through career progression. The right to access flexible working arrangements is currently a hot research topic within professional bodies, looking into how women in the workforce are treated when seeking a more adaptable employment agreement.

A report released by the Law Institute of Victoria[5] on discrimination faced by women in the legal profession looked specifically at this question at length. Of the 421 female practitioners who responded to the survey, 149 (35.4%) had made a request for their employers to allow them a flexible working agreement so that they could meet their responsibilities as a parent or carer. 79% of respondents had their request approved in full, 16% had their request partially approved and 5% reported having their request refused.

The Australian Work and Life Index released a report[6] in 2014 that discussed the impact of flexible working arrangements on the employment cycle. In addition to the length of a working day, another crucial dimension of working time in relation to health and wellbeing is the extent to which the length and scheduling fit with a worker’s needs, preferences and circumstances. Employee-centred flexibility, in which workers have some input and control over the scheduling and length of their work hours and location of work is an important resource for employee wellbeing.

The Fair Work Amendment Bill 2013 extends the right to request a flexible work arrangement to all workers with care responsibilities (and workers in certain other circumstances such as those with a disability or aged 55 years or older). Whilst extended inclusion criteria are an important step in supporting all workers with care responsibilities for children or adults, it remains a relatively fragile entitlement as the right to request does not have any instrument of appeal in order to contest an employer’s refusal if it should be unreasonable.

There is good evidence that flexible work practices would benefit the health and safety of all workers, whether they have care responsibilities or not. There is a case for extending the right to request flexible work arrangements to include all workers regardless of their circumstances. However, such an extension will only be meaningful if workers who have their requests refused or do not make such requests because they lack workplace power, are backed up with a meaningful appeal mechanism.

In 2016, The Association of Corporate Counsel, a global bar association, published a report called “Cause and Effect: Why Women Leave The Legal Profession”[7] which showed, quite conclusively, that women in leadership positions is quite simply good business. Female stewardship is shown to have a positive impact on both innovation and revenue. A direct quote from this paper stated that “both Fortune Magazine and The Wall Street Journal reported that women do indeed contribute to positive business outcomes, offering a wider variety of critical skills to their company boards in important areas, such as governance and risk management“

Another area ripe for reform is the way that superannuation is handled in divorces. At present the Family Court of Australia is quite limited in the way they can deal with the splitting of superannuation entitlements in a divorce settlement. The Family Court is only imbued with the legislative power to deal with property that is owned by the parties as at the date of the hearing[8]. As superannuation is payable only on retirement, or some other qualifying event, it is not considered as ‘property’ for these purposes, unless benefits have been paid[9].

The Family Court has tried to escape these limits on their legislative powers in two unique ways[10]. The first, sometimes called offsetting, is an ‘adjustment of non-superannuation assets’. This entails increasing the dependent spouse’s share of presently existing property in order to compensate for the loss of future superannuation rights of the other party.

The second entails adjourning part of the property proceedings until the superannuation benefits become payable, and then making an order with respect to those benefits once they become payable.

Neither approach seems entirely satisfactory, fair or equitable. Offsetting assumes that the liable spouse has sufficient assets to make good the other’s loss of superannuation rights, and it is not a guarantee of an adequate retirement income for the recipient. Adjournment means that these particular monetary issues between spouses remain unresolved, often for many years after their divorce is finalised. Moreover, the payment of any benefits is entirely dependent on events outside the control of the liable spouse. For example, under the terms of some schemes, a wife would lose entitlement altogether if the husband dies before he becomes entitled to the benefits, since earmarking does not give her a share of his superannuation in her own right.

There are a litany of reasons behind why, what is prima facie an equitable system, actually creates disadvantages and discriminatory rules that do not fully account for the working cycle of a woman, taking into account the varying stages that women will oft be forced to or choose to go through. The Senate Economics References Report[11] makes 19 recommendations to the Australian Government to make the system more reasonable in meeting the needs of Australian women, taking in to account their work/life patterns.

The first recommendation that was made by the Senate Committee is one that bears examining as a way to introduce changes to the current system.

The committee recommends that the Australian Government review the Fair Work Act 2009 to determine the effectiveness of Equal Remuneration Orders in addressing gender pay equity, and consequently in closing the gender pay gap. The review should consider alternative mechanisms to allow for a less adversarial consideration of the undervaluing of women’s work.

The Senate Committee came to the conclusion on this recommendation that over the last two decades the gender pay gap has been unchanged but to effect change will require a sincere and ongoing effort. Many Australian organisations are becoming quite proactive in instituting measures to address the gender pay gap and setting targets for women in leadership roles. However, only 20% of Australian business reported to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency that they had introduced strategies to address the gender pay gap. There is perhaps a need for more government funded resources and analysis mechanisms to reach the other 80%.

It is telling that the Committee (which Committee? The AoCC? The Senate Committee?) reported that many of the submissions they received asserted that the current legislative superannuation tax concessions are not only poorly targeted but further serve to reinforce the gender retirement savings gap. Current tax concessions were perceived as being disproportionately targeted to disadvantage women and only serve the interests of high income households.

The current concessions only make the superannuation savings gap worse rather than effect any meaningful change to the gap and do not centre enough on facilitating better outcomes for women in retirement. The Committee took the view that the superannuation tax concessions should be reviewed in order to be more fair, efficient and equitable.

There are many ideas for reform to the system, from achievable to the somewhat idealistic and unsustainable. Over the last decade, many organisations have lobbied the Government in an attempt to bring the system to some harmonious balance, to preempt the situation where more than half our population are left in near or total poverty in their retirement, unable to afford the most basic care and expenses that our retirement income savings system was designed to address.

The issue of disparity of outcomes between men and women when it comes to retirement savings is far from a small problem, nor is there a tidy solution that encompasses the issues only touched on above. The one consensus is that reform is desperately required. We find ourselves with a rapidly ageing baby boom population in Australia, many of whom did not adequately plan for their retirement. We are at risk of the levels of poverty among older single female retirees reaching epidemic proportions.

[1] Australian Human Rights Commission, 2009 Accumulating poverty? Women’s experiences of inequality over the lifecycle: An issue paper examining the gender gap in retirement savings

[2] Ross Clare, Retirement Savings Update (2008) p3. At http://www.superannuation.asn.au/Reports/default.aspx

[3] Rebecca Cassells, Riyana Miranti, Binod Nepal and Robert Tanton, She works hard for the money: Australian women and the gender divide, AMP.NATSEM Income and Wealth Report issue 22 (2009). At http://phx.corporate-ir.net/External.File?item=UGFyZW50SUQ9MjA5fENoaWxkSUQ9LTF8VHlwZT0z&t=1

[4] Australian Human Rights Commission, Submission 36, pp. 1–2

[5] Victorian Equal Opportunity & Human Rights Commission, “Changing the rules: The experiences of female lawyers in Victoria”, (2012) at https://www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au/index.php/our-resources-and-publications/reports/item/487-changing-the-rules-–-the-experiences-of-female-lawyers-in-victoria

[6] The Persistent Challenge. Living, Working and Caring in Australia in 2014, Skinner, S and Pocock, B. Centre for Work and Life, University of South Australia

[7] Richardson, V and Myers, M. “Cause and Effect: Why Women Leave the Legal Profession” 2016 http://www.acc-foundation.com/foundation/loader.cfm?csModule=security/getfile&pageid=1440081&recorded=1

[8] (Family Law Act 1975, s.4(1)).

[9] (In the marriage of Crapp (12979) 5 Fam LR 47).

[10] (Harrison and Harrison (1996) 20 Fam LR 322; Finlay et al. 1995:295-299)

[11] The Senate Economic References Committee, ‘A husband is not a retirement plan’: Achieving economic security for women in retirement. April 2016